Should Podcasts Only Be Free Or Is Luminary Just a Bad Product?

Is the only model for podcasts free? Or, is there a model out there that makes sense for people to actually pay for an audio relationship?

That’s the central question that the founders of Luminary thought they had the answer to when they launched. Fresh off a $100 million fundraising, the founders went off to build the Netflix of podcasts, believing that there was a market for paid, ad-free podcasts.

It doesn’t appear to be working all that well. According to a Bloomberg story:

A year later, Luminary is still struggling to live up to those grand ambitions. Over the last 90 days, the company hasn’t cracked the Top 500 entertainment apps in the U.S. in average daily iPhone downloads, according to the mobile insights and analytics firm App Annie. A few notable creators, including former Obama adviser David Axelrod, have recently left the service. And several podcasters who have worked with Luminary said that few people seem to be listening to their shows, despite being given big budgets and creative freedom.

Bloomberg says that the app has only been downloaded 200,000 times in the U.S., referencing analytics provider App Annie, but Luminary says just shy of 800,000. With talent leaving, it’s clear that whatever the numbers actually are, people are simply not interested in the content that is being produced enough to actually pay the monthly rate.

My issue with Luminary is has attempted to solve a problem that doesn’t exist. Over the past few years, we’ve seen few companies launch with a thesis that relying on advertising is bad. The subscription was the future, they said. The Athletic, Substack and, of course, Luminary have all taken this stance.

In some respects, they are right, but it needs to be more nuanced than that. Hyper-targeted, 3rd-party cookie-reliant advertising might be going the way of the dodo, but that doesn’t mean all advertising is going away.

For podcasts, advertising actually fits nicely. There’s a natural flow with it and for some podcasts, the ad is actually additive. I’ve enjoyed listening to some podcast ads, whereas I’ve almost never enjoyed a banner ad. Even The Athletic, which is pretty anti-ad, sees podcast ads as normal. In an interview with Bloomberg last year:

“It generally is a part of free podcasts and we’re comfortable with that,” Mather [CEO] said. Athletic readers, he said, can rest assured that this is not the beginning of ad creep on the site. “We may experiment with advertising on free products, but our subscription product is absolutely sacrosanct.”

The other issue, and this is more anecdotal than anything, is that celebrities that have success in one medium (such as TV or video) don’t immediately translate into success with audio. There’s a relationship that builds with podcasts and I get the feeling Luminary didn’t think this existed.

It went out and paid a lot of expensive people a lot of money to launch exclusive shows on the network. The rationale? That person is famous, so they must be able to pull a big audience. However, let’s think about this. Most famous people have not had a direct relationship with their audience; it’s more indirect. They haven’t asked for money before; it’s just been given to them through intermediaries.

That’s why a show hosted by Trevor Noah or David Axelrod won’t take off. Both may be famous—one for having a TV show, one for helping Obama become President—but neither of them has ever built a 1:1 relationship with a listener. That’s a prerequisite to these sorts of products.

And that’s where Luminary failed. It assumed that people were just signing up to binge listen to content the same way people do for Netflix. But in personality-driven media, I don’t think that model works.

All of that said, I do think there is an environment for people to pay for podcasts directly. Let me build a relationship with the listener and then try and convert them to become paid.

People are actually comfortable with data collection

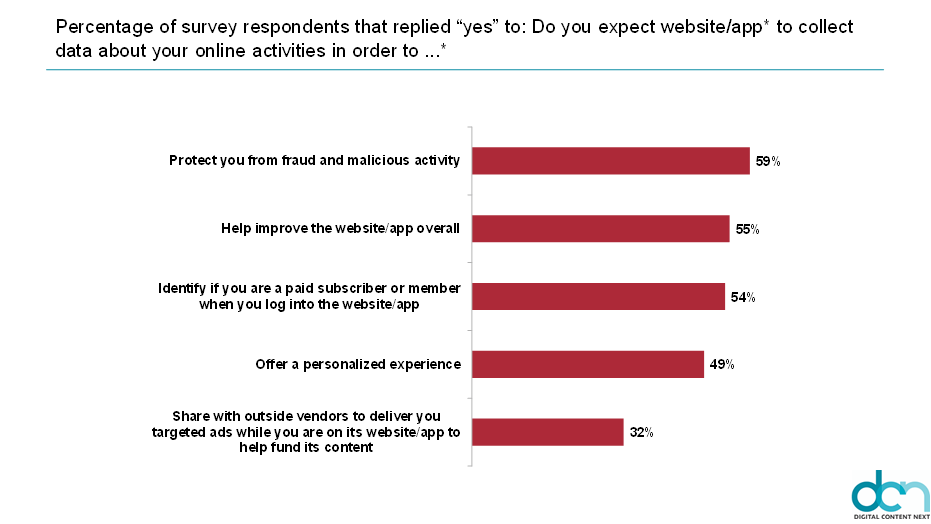

According to a survey conducted by Digital Content Next, people are comfortable with data collection with one exception:

Overall, consumers expect websites and apps to collect data about them to personalize, protect and improve their experience. In sharp contrast, consumers do not expect outside vendors to collect data about them for reuse or sale.

The results can be seen in the chart below:

It’s good to see that users are comfortable with publishers collecting data on them to make the experience better. I’ve been advocating for a while now that publishers should be collecting as much information about their users as they can.

There are two reasons for this.

First, the more you know about how your audience, the better informed you can be regarding product development. I’m not talking about anonymous data like pageviews and things like that. I want to know what types of people are coming to the site. What is their profile? Who are they? That informs the types of products we should be building.

Second, the more you know, the better the advertising can be. You can provide your advertisers with the opportunity to target specific segments of your site. If you know who they are and how they are engaging with your site, you can then deliver advertising to those specific people. The technology exists to do this today, but historically, publishers have relied on 3rd party ad tech companies to accomplish it. With these privacy laws, we’re going to need to take control of the technology where it makes sense.

According to the chart, only a third of respondents are comfortable with their data being shared with outside vendors to deliver targeted ads. This is why we need to take control over our technology.

We need to start developing ad products that give marketers the ability to target while also not relying on 3rd parties to give us the data. Coupled with 3rd party cookies going away, we need to get to work now to build out the correct systems and ad buying tools to ensure we can keep an ad business going.

I think this is the scenario The Washington Post’s Zeus product is trying to solve for. We need an easy way to collect the right data about our users and then give marketers the ability to advertise to the right people. I’m not explicitly saying publishers should start licensing expensive technology, but to give marketers the tools they need, use them as a reference. As I wrote in a previous piece, they’ve got three offerings:

Zeus Insights: This is the contextual targeting component of the platform. As an advertiser, what sort of readers do you want to target? Said another way, what kind of content do you want to target, which you believe your target audience will be consuming?

Zeus Performance: This is the ad analytics platform. Advertisers are going to want real-time, high quality data to determine engagement around the actual advertisements.

Zeus Prime: These are premium, social-type advertisements. You can drop in a tweet, Facebook post, or Instagram post and then the ad is automatically created. You then add a CTA underneath it and voila, without having to design or code it, you’ve got a great looking advertisement. To achieve these high quality ads, The Washington Post partnered with Polar.

If publishers are smart with their user data collection, they can learn more about their audience, make better product decisions and deliver better advertising with the caveat that the publisher, ultimately, will be responsible for that delivery—we can’t rely on 3rd parties anymore.