A Deeper Dive Into What Really Damaged Newspapers

Benedict Evans, formally of A16Z and now analyzing solo, released a piece yesterday, News by the ton: 75 years of US advertising, and it’s a deep analysis into the numbers surrounding the newspaper business.

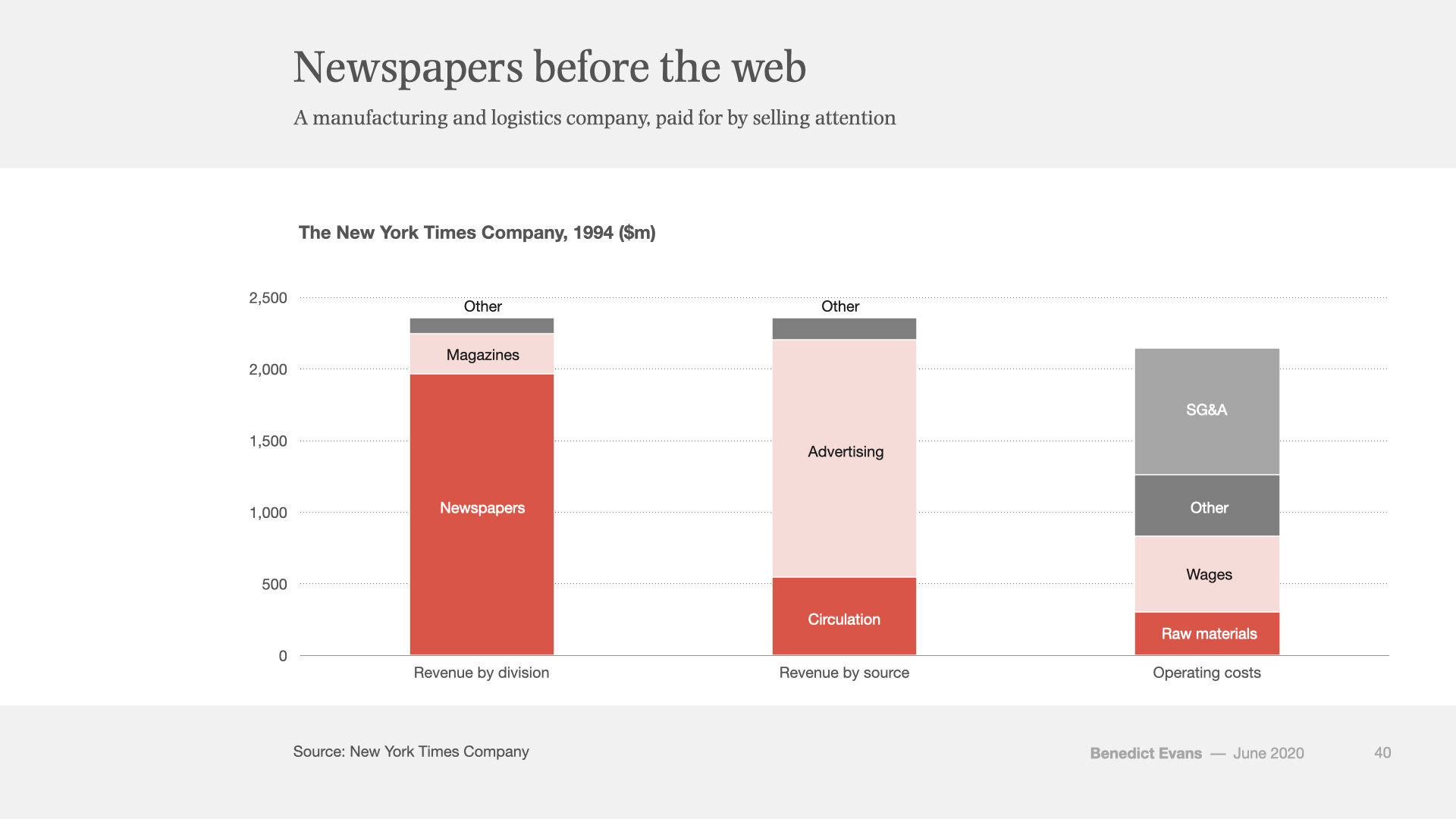

At its core, Evans argues that what has killed newspapers is a manufacturing discussion more than anything else. He sums it up nicely in this single chart:

In 2000, the industry shipped 12.5m tons of newspaper. In 2018, it only shipped 2.5m tons. What changed?

But it’s also because newspapers were an oligopoly, and they lose that oligopoly online. Newspapers are, yes, a content business, but they were also a light manufacturing business, and it was the replacement of light manufacturing and trucking with bits that removed the barrier to entry and unbundled their attention.

It’s true, newspapers had it all. They controlled the writing, printing, ad sales, circulation and distribution all in one building. It was easy. Because newspapers were the only game in town, if you wanted news, you had to go to your newspaper.

It’s not Facebook and Google that changed that, though. The internet itself fundamentally altered the gate keeper. Thirty five years ago, if I wanted to launch A Media Operator, it would have been a print newsletter that I sent you in the mail. I’d have printing and shipping costs, which would bring my margins down quite considerably.

You can see that in another chart that Evans has:

The New York Times did about $2.4 billion in revenue in 1994 (Evans used this year because it’s the year Netscape was released). However, the cost of that revenue was probably close to $2.2 billion. That’s a 9% margin. Consider A Media Operator? I’m a solo operation and I pay Substack 10%. My margin is far higher and that’s because of the tools available to me.

The internet made it possible for anyone to enter the publishing world. There were considerable fixed costs to getting started 30 years ago, but now, it’s as easy as buying a domain name, hooking up some hosting and writing.

Did Facebook and Google exacerbate that? Of course they did. It was suddenly very easy to find content on the internet. You didn’t have to stick with your one, local paper. Instead, you could find that content anywhere.

The means of distribution changed. It is very easy to generate revenue when you’re the only player in town. That changed with the internet and newspapers took a very long time to fundamentally change.

That doesn’t mean they can’t change, but so far, there has been a general unwillingness to look at the real problem. Rather than throwing out audacious claims like Facebook and Google should pay us for the right to send us traffic (which I’ll touch on again in a little bit), we should, instead, be looking at finding ways to deliver value to our readers and ad partners in a way that platforms can’t.

Last month, I posed the question: Should Local Be Thinking More About Data? It’s about halfway down that post.

In it, I summed up the following:

For example, let’s say there was a publication covering Dutchess County, NY (where I grew up). It’s got a population of 294,000. That’s not a terrible size for a local publication.

A reporter might report on the latest bill that the local politician is voting on. However, rather than writing an in-depth piece, this publication could build a database called “Dutchess Political Tracker” that tells me everything about what my elected officials specifically are doing. There are multiple towns and small cities in Dutchess, so each mayor would be covered too. Imagine how rich that could become.

That doesn’t mean there would be no reporting. Of course that’s to be expected and doing deep, investigative work remains an important part of the local reporter. However, if local news is meant to serve the community, providing updates on what’s happening in a structured data format versus long-form story might be a better experience for everyone.

Rather than having journalists regurgitate basic facts, display them in a structured data format. Let’s use an example…

Say there is a bill proposing repaving the major highway in the county. It’s going to cost $50 million, which you are paying for as a tax payer. Build a basic page that has the issue up top, the representative’s name, picture and whether they are voting yes or no. Maybe include a link to that representative’s website so people can quickly go complain one way or the other.

Do this with every issue that is coming to a vote in your local jurisdiction. This is the kind of information that people want to pay for. They want to know what’s going on in their local government more than they want to know anything else.

According to the Shorenstein Center and Lenfest Institute white paper Digital Pay-Meter Playbook:

The Business Case for Local and Unique Content: According [to] the publishers surveyed, users who view local news appear to be 2-5 times more likely to subscribe than those who view national and wire-sourced stories. Critically, our analysis identified a correlation between subscription sales and amount of local content produced by the publication, reinforcing the business case for local reporting.

In the quest to generate ad revenue, local papers started producing far too much national news. I go to The New York Times for that. Local papers need to stop competing on fluff national content and, instead, focus on your geographic region. Cover the hell out of that region. Give them unique data packages to help them make informed voting decisions. And then give your journalists the liberty to hunt down the people that are taking bribes.

One final note worth covering from Evans piece. We like to say that Facebook and Google took ad revenue from the newspapers. And to some extent, they did. However, something else happened.

Going back to 1950, there has never been a time when US ad spend as % of GDP dropped below 1%. In many respects, it was comfortably resting at approximately 1.25%. Once the financial crisis happen, it never got above 1% again.

What changed? Two things come to mind.

First, the quality of advertising improved considerably with the rise of Facebook and Google. Both companies provide incredible reporting and the ability to gauge whether an ad campaign was successful. Print ads, on the other hand, had no real reporting. You bought it, maybe did a sentiment survey, and moved on with your life. With the internet, CFOs could finally look at the marketing department and question whether all that money being spent was worth it.

Second, when there are fewer companies in existence, there is less demand for advertising by default. What do I mean? I have a friend who used to work at CNBC during the dotcom bubble. There were so many startups all trying to build their business that the ad sales team was crushing it. But as time went on and those companies went out of business or were acquired, the need for large ad budgets reduced. You spend a lot in advertising when you’re competing. When competition goes away, you don’t have to spend as much.

It’s not going to get any better either, with how things are looking. This is a good chart from Quartz that shows what’s happening.

If that number doesn’t start trending up, we shouldn’t expect US ad spend as % of GDP to rise either.

The economy is interconnected. There are a lot of reasons newspapers have died off. Some were out of their control. I imagine a future where there are plenty of local publications that serve their communities with smart reporting, structured data sets around important issues and great ad products for marketers.

Speaking of…

Sponsor

If you don’t know who MrBeast is, you probably should. His real name is Jimmy Donaldson, and he’s a 22 year old YouTube creator.

In 2012, Jimmy started making content about the popular video game Minecraft.

Today, he has over 37 million subscribers. That’s six times the number of people that subscribe to The New York Times.

Jimmy Donaldson and creators like him are ushering in a new era of media and pop culture.

The team of analysts at Trends identified 30 brands that, like MrBeast, are helping to define the future of media. They profiled each with detailed data on how they originated, what their reach is, and what makes them so successful.

To get access to the full report and two weeks of access to the Trends database, sign up for a $1 trial with Trends today.

Facebook couldn’t care less about Australian rule

The new tactic from publishers is to try and get Facebook and Google to pay for the right to send us traffic. The argument is simple… Facebook and Google, in the publishers’ minds, are making money on the headlines and snippets that publishers create, so they should share in the money.

I haven’t hidden my irritation with this strategy. I feel it boils down audience ownership.

A user that types www.amediaoperator.com into their browser is likely my audience. Why? I have done a good job getting them to know the brand. Even a user that types A Media Operator into Google and then clicks over could be argued as my audience.

However, when a user goes to Google and does a search for a certain topic and then clicks over to the publisher, that is not the publisher’s audience. That person is Google’s audience and Google is doing its job to direct users to the right kind of content. As the publisher, we are borrowing that user.

Users that are coming from Facebook and Google are not our users. Not yet at least. They could become our users if we do a good job converting them. But they’re not actually our users.

Now let’s jump to Australia…

Back in April, The Guardian reported that the Australian Treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, had asked the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) to propose a code between platform and media company that would:

…require the companies to negotiate in good faith on how to pay news media for use of their content, advise news media in advance of algorithm changes that would affect content rankings, favour original source news content in search page results, and share data with media companies.

In May, the ACCC released a concepts paper that included a section titled Collective boycott or ‘all in/none in.’ In this, the ACCC wrote:

An alternative bargaining framework may allow commercially funded news media businesses to put in place a collective boycott if commercial negotiations are unsuccessful. A collective boycott, or the threat of a collective boycott, may encourage each of Google and Facebook to offer news media businesses more appropriate remuneration for the use of their content.

This bargaining framework could be incorporated into a bargaining code by including mechanisms preventing each of Google and Facebook using news published by all (or a significant subset of) news media businesses in the absence of commercial agreements with each of these businesses. A level of compulsory participation in this collective boycott is likely necessary for this mechanism to be effective, as without the participation of all (or at least a majority) of prominent news media businesses, each platform may circumvent the collective boycott by reaching agreements individually with one or two large publishers, undermining the bargaining power of the remaining group.

To sum that up? The publishers are basically telling Facebook and Google that if they don’t pay, all news will be removed from their platforms entirely. It’s only a concept right now, but it’s still an interesting one.

Which brings us to Facebook’s response…

According to The Guardian, in a submission to the watchdog, Facebook said:

“We made a change to our News Feed ranking algorithm in January 2018 to prioritise content from friends and family,” the company said. “These changes had the effect of reducing audience exposure to public content from all pages, including news.

“Notwithstanding this reduction in engagement with news content, the past two years have seen … increased revenues, suggesting both that news content is highly substitutable with other content for our users and that news does not drive significant long-term value for our business.

“If there were no news content available on Facebook in Australia, we are confident the impact on Facebook’s community metrics and revenues in Australia would not be significant.”

In other words… Facebook couldn’t care less if the news media boycotts. A boycott works if the boycotted really wants what you have. If they don’t, you’ve got a problem.

To make matters worse:

Facebook said it had sent 2.3bn clicks to Australian news publishers in the five months from January to May 2020, which they estimated to be worth $195.8 million to the news organisations.

I certainly want media companies to be paid for what they deserve to be paid for. There is no denying that. However, this is a classic case of publishers wanting to eat their cake and have it too. Publishers want to be paid to receive traffic. That’s not rational.

We’ll see where this plays out, but if I had money on Australian media, I’d say that the media companies back down from this concept of a boycott. If Facebook really won’t lose any money, it won’t blink; whereas, publishers will absolutely lose money.